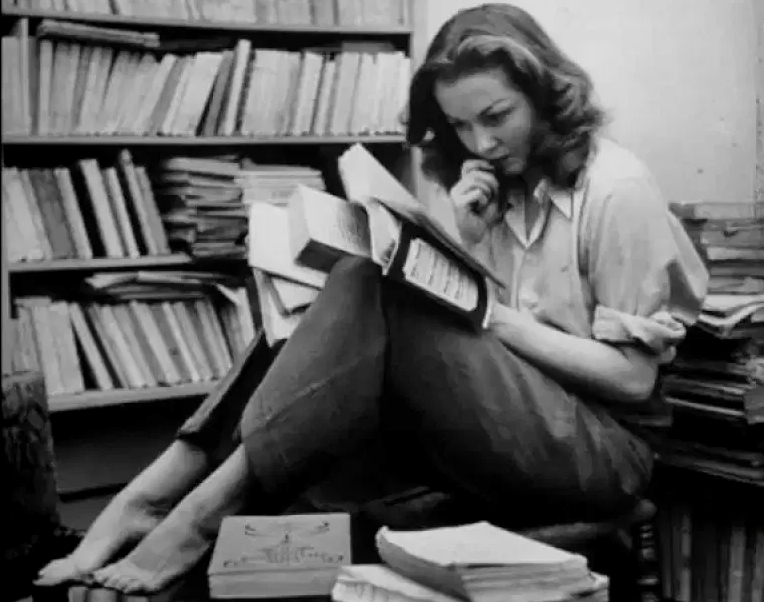

Sylvia Plath’s life has been marred by conspiring thought surrounding her death and her husband, Ted Hughes whom was essentially blamed for her death. All the while, the whole time — while she was alive — all Sylvia wanted, was to be in love and write poetry. Sylvia Plath was a true poet, who in retrospect must now be given the full respect she deserves as a talented poet of depth and character unparalleled by many of her generation.

Sylvia Plath could see life as it happened. She felt the universe revolve around the events of her days and she was forever tormented by why her father died — her poetry was borne of her deepest oceans, her wild currents and highly ambitious and ravenous nature and determination and to be a voice — not only for women, but for a world who seeks knowledge and enquires as to why death can arrive so soon, unbounded and un-invited and almost, simultaneously, feeling a wanton of death to arrive and to speak of it’s true nature in our existence. I do not classify Sylvia’s fascination with death as any morbid structure of her psyche—I see it in her poetry as an openness to the event of death and it’s meaning in our lives.

In her final book of powerful poetry, Ariel, the one most popular and which stands out, is Daddy. It is a remarkable poem as it declares her long undying grief at her father’s premature death—when Sylvia was only 9 years old. The poem, is an exit to this grief held.

Jaymz Hawkes

Daddy

You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe

In which I have lived like a foot

For thirty years, poor and white,

Barely daring to breathe or Achoo.

Daddy, I have had to kill you.

You died before I had time —

Marble-heavy, a bag full of God,

Ghastly statue with one gray toe

Big as a Frisco seal

And a head in the freakish Atlantic

Where it pours bean green over blue

In the waters off beautiful Nauset.

I used to pray to recover you.

Ach, du.

In the German tongue, in the Polish town

Scraped flat by the roller

Of wars, wars, wars.

But the name of the town is common.

My Polack friend

Says there are a dozen or two.

So I never could tell where you

Put your foot, your root,

I never could talk to you.

The tongue stuck in my jaw.

It stuck in a barb wire snare.

Ich, ich, ich, ich,

I could hardly speak.

I thought every German was you.

And the language obscene

An engine, an engine

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

I began to talk like a Jew.

I think I may well be a Jew.

The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna

Are not very pure or true.

With my gipsy ancestress and my weird luck

And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack

I may be a bit of a Jew.

I have always been scared of you,

With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo.

And your neat mustache

And your Aryan eye, bright blue.

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You —

Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

You stand at the blackboard, daddy,

In the picture I have of you,

A cleft in your chin instead of your foot

But no less a devil for that, no not

Any less the black man who

Bit my pretty red heart in two.

I was ten when they buried you.

At twenty I tried to die

And get back, back, back to you.

I thought even the bones would do.

But they pulled me out of the sack,

And they stuck me together with glue.

And then I knew what to do.

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

And a love of the rack and the screw.

And I said I do, I do.

So daddy, I’m finally through.

The black telephone’s off at the root,

The voices just can’t worm through.

If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two —

The vampire who said he was you

And drank my blood for a year,

Seven years, if you want to know.

Daddy, you can lie back now.

There’s a stake in your fat black heart

And the villagers never liked you.

They are dancing and stamping on you.

They always knew it was you.

Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.